Empower Your Breast Health: A Guide for Women

Breast cancer is the most common cancer for women, but finding it early can lead to better treatment and excellent results. Taking care of your breasts is a big part of staying healthy, and knowing your body helps you notice changes quickly and act with confidence. Being aware of your breast health means learning what’s normal for your breasts, understanding how they might change, and watching for signs like lumps, skin changes, or liquid coming from your nipple. Understanding your risk of breast cancer also helps you make smart choices about your health. Eating healthy, staying active, and using proven check-up methods can lower your risk. New tools, like artificial intelligence, are also helping make these check-ups even better.

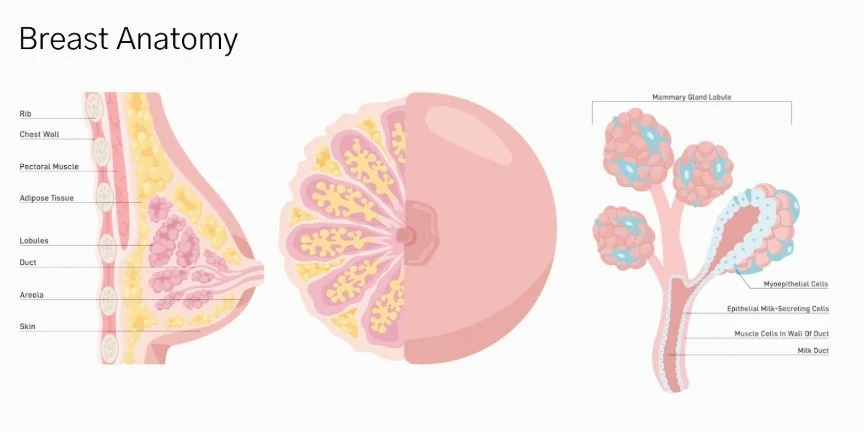

The breast is a glandular organ consisting of the glandular tissue (the milk ducts) connective tissue and adipose tissue (fat). The breast is anchored to the skin and pectoral fascia by Cooper’s ligaments and is richly supplied by blood vessels, nerves, and lymphatics

Figure 1: Breast Anatomy: Lobes Each breast has between 15 to 20 lobes, or sections. These lobes surround your nipple like spokes on a wheel. Glandular tissue (lobules) These small sections of tissue found inside lobes have tiny bulblike glands at the end that produce milk. Milk (mammary) ducts These small tubes, or ducts, carry milk from glandular tissue (lobules) to your nipples. Nipples The nipple is in the center of your areola. Each nipple has about nine milk ducts, as well as hundreds of nerves. Areolae The areola is the circular darker-colored area of skin surrounding your nipple. Areolae have glands called Montgomery’s glands that secrete a lubricating oil. This oil protects your nipple and skin from chafing during breastfeeding

Your breasts grow and change because of hormones, which guide them through different stages of life. From childhood to middle age, they keep adapting. During pregnancy and breastfeeding, hormones like prolactin enable your breast to produce milk. After breastfeeding, they slowly go back to a resting state. After menopause, they settle into a new pattern as hormone levels even out.

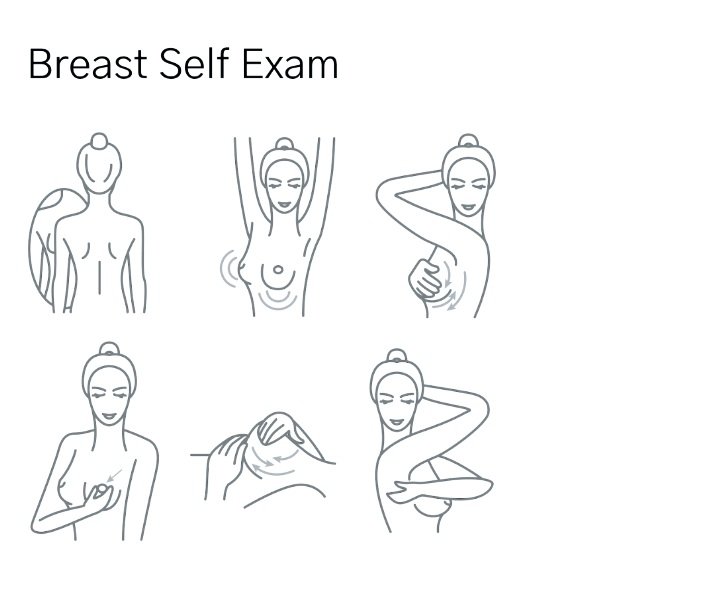

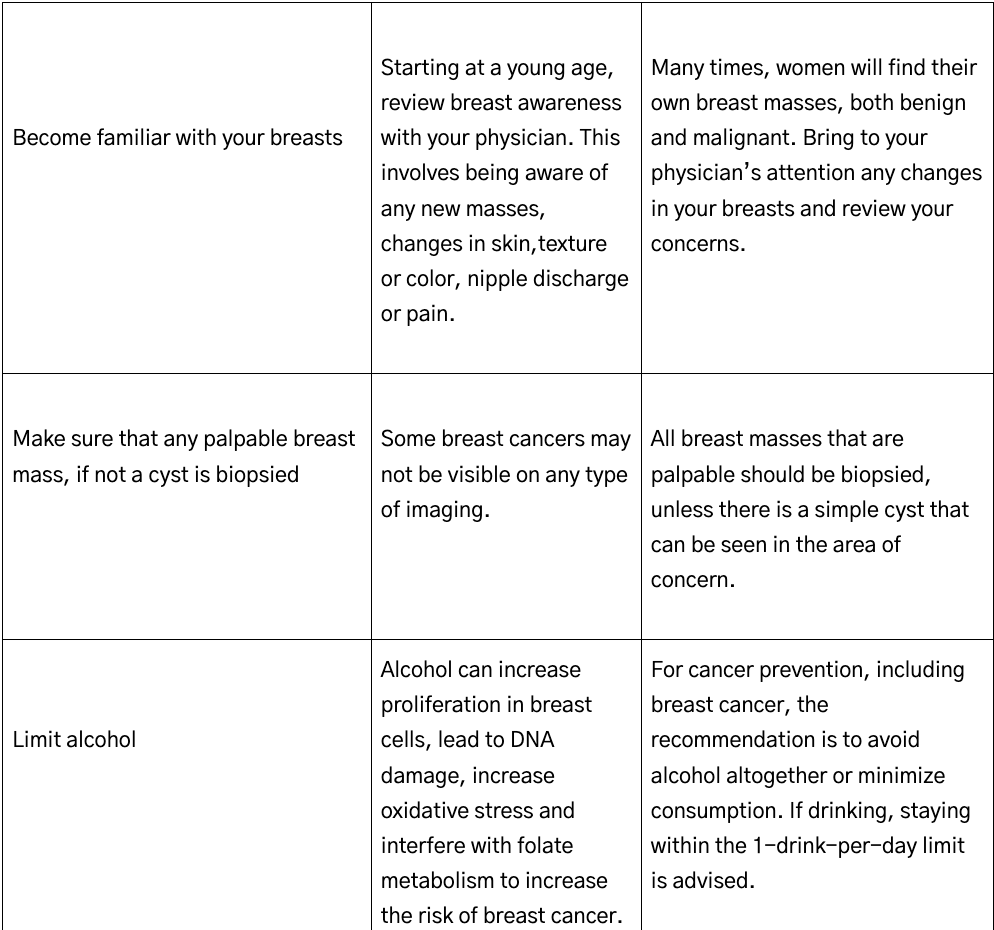

Breast awareness means knowing what’s normal for your breasts by regularly checking how they look and feel. This helps you notice changes like new lumps, dimpled skin, nipples that pull inward, or anything unusual. Being aware empowers you to spot these changes early and tell a doctor so they can check it out and suggest next steps. It also means teaching young girls about their bodies so they feel comfortable with them. Breast awareness includes learning about cancer screening, like mammograms, and ways to keep your breasts healthy, such as eating well, exercising, and drinking less alcohol. It’s also important to know your risk of breast cancer based on your family history, genetics, or personal health.

Breast Self-Awareness

You do not need to follow a set schedule or use a special technique to check your breasts. Just be aware of how your breasts usually look and feel, and report any changes right away. Regular mammograms and clinical breast exams are still important for screening, depending on your age and risk factors. Talk to your healthcare provider about the best screening plan for you.

Figure 2: Breast Self-Exam and Awareness Guide Breast awareness means regularly checking your breasts to understand how they normally look and feel, so you can notice any changes early. To do a breast self-exam, start by standing in front of a mirror with your arms relaxed to check for any changes, like dimpling, redness, or nipple changes. Next, raise your arms and look again for the same things. Then, lie down and use the pads of your fingers to feel each breast in a circular motion, covering the entire area from your collarbone to your upper abdomen and from your armpit to the center of your chest. Press gently but firmly to feel for lumps or thickened areas. Finally, gently squeeze each nipple to check for any discharge. Breast awareness also includes: changes in the size, shape, or appearance of the breast; unexplained pain in one area of the breast; nipple discharge (other than breast milk), especially if it is bloody; redness, scaliness, or swelling of the breast or nipple; knowing your risk of breast cancer based on family history, genetics, or personal health, and supporting your breast health through healthy eating, exercise, and limiting alcohol. If you notice anything unusual, review with a physician right away.

Common Breast Health Issues

Benign breast conditions are the most frequent breast health issues encountered by women. Fibrocystic changes, cysts, and fibroadenomas are the most common benign lesions.

Fibrocystic changes in the breast are a common, benign condition that many women experience, characterized by the development of fibrous tissue and fluid-filled cysts that can make breasts feel lumpy or rope-like. Fibrocystic changes in the breast are considered a normal anatomic variant and are not associated with an increased risk of breast cancer. These changes are seen in up to 50% of women over age 30 and are influenced by hormonal fluctuations, particularly during the menstrual cycle, pregnancy, or perimenopause, as estrogen and progesterone levels shift. Hormonal influences cause the breast tissue to become denser or more prone to cyst formation. Symptoms may include tenderness, swelling, or discomfort, often most noticeable before your period, though the severity varies from woman to woman. While the impact of diet on fibrocystic changes can vary for each woman, some foods may potentially worsen symptoms due to their influence on hormone levels or inflammation. High-caffeine options like coffee, tea, chocolate, and energy drinks might increase breast tenderness or cyst discomfort in some cases. Additionally, high-fat foods, especially those rich in saturated fats (like red meat or fried items), and excessive salt intake could contribute to swelling or bloating, amplifying discomfort. Limiting these and opting for a balanced diet with more fruits, vegetables, and whole grains may help ease symptoms for some. Additionally, a diet rich in antioxidants like vitamin C and iodine (from seaweed or supplements, under guidance) could support breast health. Certain supplements may help ease fibrocystic breast changes for some women, though evidence varies. Vitamin E (around 400 IU daily) is often suggested to reduce breast tenderness, while evening primrose oil (containing gamma-linolenic acid, 1,000-3,000 mg daily) may help with inflammation and discomfort. Chasteberry (20-40 mg daily) is another option that can potentially lessen symptoms. Results differ, so personalized is key. Birth control pills can sometimes influence fibrocystic changes in the breast, but the effect varies from woman to woman. These pills contain hormones like estrogen and progestin, which can alter breast tissue density and fluid retention, potentially worsening symptoms such as tenderness or cyst discomfort in some cases. However, for others, hormonal birth control might actually help regulate cycles and reduce severity. Since individual responses differ, it’s wise to monitor how your body feels.

Regular physical activity, like 30 minutes of moderate exercise (such as brisk walking, yoga, or swimming) most days of the week, may help to ease breast tenderness or discomfort. Evidence from a large cross-sectional study indicates that higher total lean mass (TLM), which is typically increased through regular physical activity, is associated with a lower risk of fibrocystic breast changes, while higher percent body fat (PBF) is associated with increased risk. This suggests that exercise, by improving body composition, may reduce the likelihood of developing fibrocystic changes.Additionally, physical activity is associated with favorable modulation of sex hormone levels and local breast tissue inflammation, both of which are implicated in benign breast conditions. Meta-analyses and randomized controlled trials demonstrate that exercise can modestly reduce circulating estrogens and androgens, and increase sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG), independent of weight loss. Furthermore, physical activity is linked to reduced local breast tissue inflammation and lower expression of pro-inflammatory mediators, which may contribute to a healthier breast microenvironment and potentially reduce the risk or severity of fibrocystic changes.

Simple cysts are fluid-filled and typically occur in women aged 35–50, with incidence peaking around age 50. Simple cysts of the breast are benign, fluid-filled lesions and on ultrasound. The causes of simple breast cysts are multifactorial and primarily related to hormonal influences, particularly fluctuations in estrogen and progesterone levels during the menstrual cycle, which stimulate the proliferation and involution of breast lobules and ducts, leading to cyst formation. Simple cysts do not increase the risk of malignancy and typically require no intervention or follow-up unless they are symptomatic with pain or cosmetic concerns; in such cases, aspiration may be performed for relief, and the fluid can be discarded if non-bloody. Distinguishing simple cysts from complicated or complex cystic lesions is critical, as the latter may require further evaluation or biopsy due to a higher risk of malignancy.

Fibroadenomas are the most common benign solid tumors in women under 30, presenting as well-circumscribed, mobile masses; they rarely require intervention unless symptomatic or growing. They are the most common benign breast tumors, particularly affecting women in their 20s and 30s, though they can occur at any age and are occasionally seen in postmenopausal women, especially with hormone replacement therapy. Histologically, fibroadenomas are composed of both stromal and epithelial elements, and are well defined, mobile, nontender masses, usually 1–3 cm in diameter. Diagnosis relies on a combination of clinical examination, imaging—ultrasound is preferred in younger women, with mammography added in older women—and tissue sampling via needle biopsy as clinical assessment alone is insufficient to exclude malignancy. Most fibroadenomas are managed conservatively, as they are generally slow-growing and have a low risk of malignant transformation; surgical excision is reserved for lesions that are large, symptomatic, rapidly growing, or have atypical imaging or histologic features. The risk of breast cancer associated with fibroadenomas is not significantly increased, and most lesions either remain stable or regress over time.

Breast pain (mastalgia) is a common complaint, affecting up to two-thirds of women during their reproductive years. Mastalgia is classified as cyclical (related to the menstrual cycle) or noncyclical. Cyclical pain is usually bilateral and diffuse, while noncyclical pain is more likely to be focal and unrelated to menses. Most cases are benign and not associated with malignancy. Contributing factors include hormonal fluctuations, large breast size, poorly fitting bras, and certain medications. Medications that can cause breast pain include hormonal agents such as oral contraceptives and hormone replacement therapy, as well as certain psychotropic drugs (notably selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and antipsychotics), and some cardiovascular agents (including specific beta-blockers such as atenolol). Nutrition can impact breast pain, particularly in the context of cyclic mastalgia and fibrocystic breast changes. Optimizing diet quality—emphasizing anti-inflammatory nutrients, fruits, vegetables, and healthy fats—may reduce pain severity.Lower physical activity and higher saturated fat intake may be associated with increased breast pain prevalence and severity. A nutritional formula containing gamma-linolenic acid (GLA), iodine, and selenium may reduce breast nodularity and decrease the need for pain medication in women with fibrocystic breast changes.. Abnormal plasma fatty acid profiles have been observed in women with mastalgia, and supplementation with essential fatty acids (such as evening primrose oil) can normalize these profiles, reducing pain in some women. Small trials of soy protein supplementation have shown subjective improvement in breast pain in some women. First-line management of breast pain includes reassurance, proper support, and topical NSAIDs; hormonal agents such as danazol or tamoxifen may be considered for refractory cases, though side effects limit their use.

Infections and inflammations of the breast, such as mastitis and abscesses, are most common in lactating women. Lactational mastitis presents with localized pain, redness, and systemic symptoms such as fever. Breast abscesses may develop if mastitis is not adequately treated and require drainage in addition to antibiotics. Non-lactational mastitis, including periductal and granulomatous mastitis, is less common and may require specialized management. It is also important to be aware that there is a type of cancer, called inflammatory breast cancer that can mimic an infectious process.

Breast cancer remains the most common malignant breast disease. The main types are invasive ductal carcinoma, invasive lobular carcinoma, and less commonly, inflammatory and triple-negative subtypes. Risk factors include increasing age, family history, BRCA1/2 and other genetic mutations, early age at first period, late menopause, never having children, older age at first birth, hormone replacement therapy, alcohol use, obesity, and certain benign breast diseases (especially those with atypia). Mammography is the cornerstone of screening, with additional imaging and biopsy for diagnosis.

Breast Cancer

Cancer is a group of diseases characterized by the uncontrolled growth and spread of abnormal cells that can invade and damage healthy tissues and organs. Breast cancer is a malignant neoplasm arising from the cells of the breast, most commonly originating in the ducts (invasive ductal carcinoma) or lobules (invasive lobular carcinoma). It is characterized by uncontrolled proliferation of abnormal cells, which can remain localized (in situ) or invade surrounding breast tissue and metastasize (travel) to regional lymph nodes or distant organs such as bone, liver, lung, or brain. Features, including hormone receptor (estrogen and/or progesterone) status and Her2-neu, a molecule important in the regulation of cell growth are also important in breast cancer as these subtypes have distinct prognostic implications and are treated differently.

Breast cancer is the most common cancer in women, when skin cancer is excluded. Approximately 320,000 new breast cancers are diagnosed in the United States each year. The lifetime risk for a woman to develop breast cancer is about 13% overall. It is the second leading cause of cancer death in women, and 1 in 43 women will die from breast cancer. Black women have a 40% higher chance of dying from breast cancer when compared to other ethnicities and racial groups. Concerning trends in breast cancer include that rates have been steadily increasing about 1% per year starting in 2012, with a steeper rise in younger women. The cause of this rise is unclear, but we can look to environmental exposures, nutrition and lifestyle as possible contributors.

Early-stage breast cancer is often asymptomatic, but may present as a painless breast lump, changes in breast shape, skin dimpling, nipple retraction, or discharge. Diagnosis is confirmed by tissue analyzed from a biopsy, typically following imaging.

Risk factors for breast cancer include increasing age, family history of breast cancer or related cancers (such as ovarian, prostate, or pancreatic cancer), known deleterious gene mutations (e.g., BRCA1/2 and others), and a personal history of certain breast pathologies such as atypical hyperplasia or lobular carcinoma in situ. Additional risk factors include reproductive health, not breastfeeding, higher body mass index, alcohol consumption, smoking, dense breasts on mammography, and prior exposure to high-dose therapeutic chest irradiation at a young age. Women with dense breasts on mammography have a two fold elevated risk to develop breast cancer. Certain ethnicities, such as Ashkenazi Jewish women, are at increased risk due to a higher prevalence of BRCA mutations. Pathogenic variants in genes such as BRCA1, BRCA2, PALB2, ATM, CHEK2, BARD1, RAD51C, RAD51D, and TP53 confer substantial risk, and a positive family history in first-degree relatives remains a strong independent predictor, even in the absence of a known mutation. Increasingly, polygenic risk scores are also being used to evaluate a woman's risk of developing breast, and other, cancers. A polygenic risk score is a way to estimate your chance of getting a certain disease, like breast cancer, by looking at many small changes in your DNA. Scientists know that some tiny differences in your genes can add up to increase or decrease your risk for certain health conditions. They use information from studies to create a score that combines these genetic changes into one number, showing if you’re more or less likely to develop the disease compared to others. It’s like a report card for your genes, but it doesn’t say for sure you’ll get sick—it just gives you a better idea of your risk so you can make smart choices about your health, like getting check-ups or living healthier.

Modifiable risk factors continue to be a focus of prevention efforts. Obesity, especially in postmenopausal women, is consistently associated with increased risk of breast cancer. Alcohol intake, even at moderate levels is an established contributor. Other modifiable factors include physical inactivity, smoking, and limited breastfeeding, while diabetes and hypertension have also been implicated. These findings underscore the importance of individualized risk assessment that incorporates both genetic and lifestyle factors, as well as the need for targeted prevention strategies.

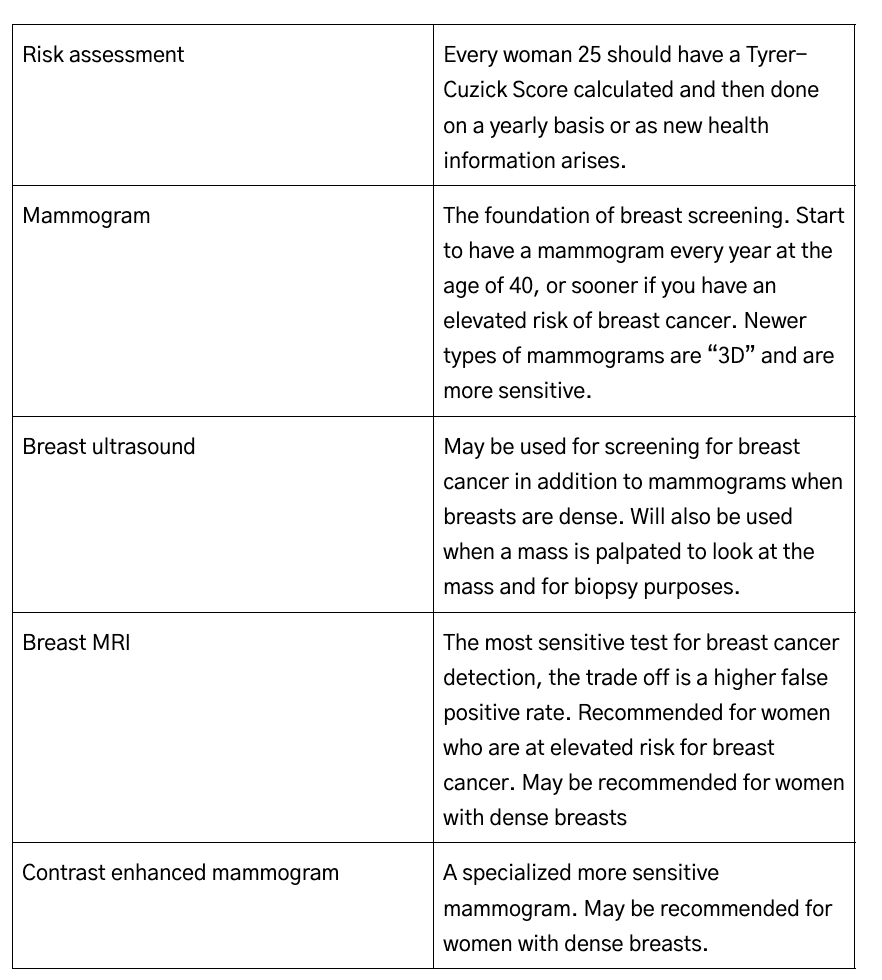

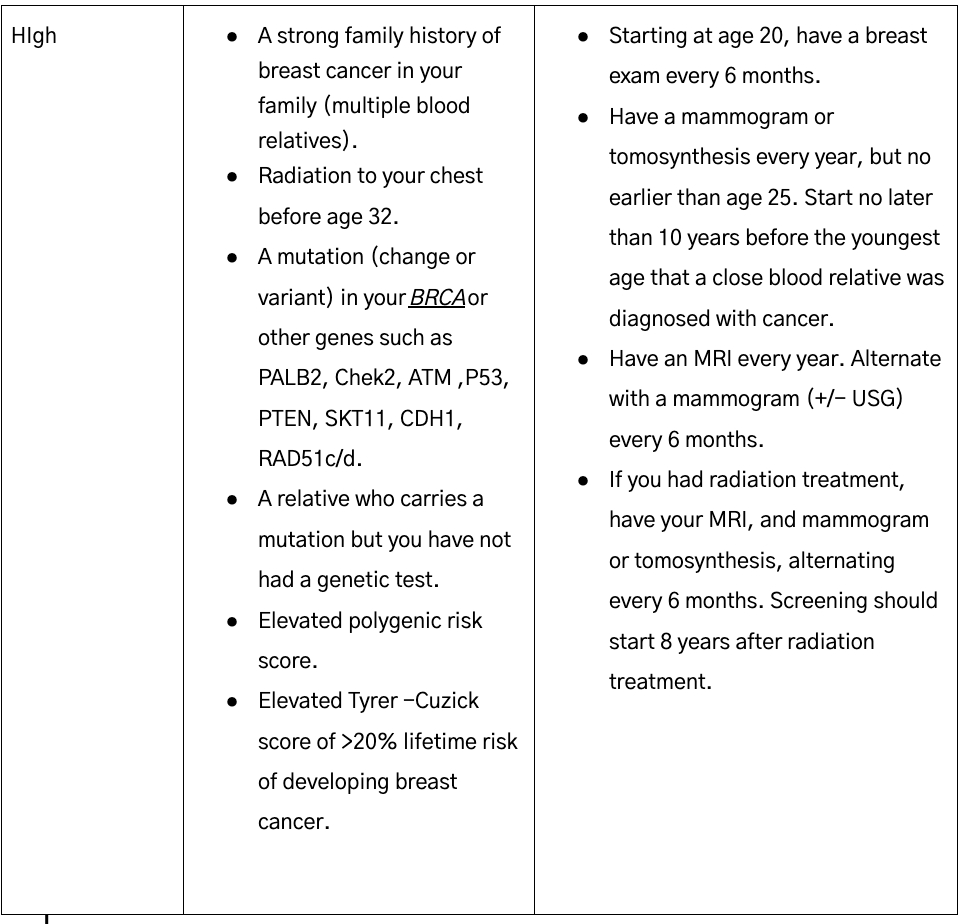

Every woman at 25 should have her lifetime risk of breast cancer calculated. This is straightforward and can be done by you online. The Tyer-Cuzick Score, also known as the IBIS risk assessment tool, is a widely used model for estimating a woman’s individual risk of developing breast cancer over her lifetime and within the next 10 years. It incorporates a comprehensive set of risk factors, including age, family history of breast and ovarian cancer, reproductive hormonal factors (such as age at menarche, menopause, and first childbirth), genetic predispositions (like BRCA mutations), and personal health factors (such as body mass index and history of benign breast disease). By integrating these variables, the Tyrer-Cuzick model generates a personalized risk score that helps guide decisions about preventive measures, such as enhanced screening with MRI of the breast in addition to mammography, medical prevention strategies, and lifestyle modifications. Its detailed approach and ease of use makes it particularly valuable for identifying women at high risk who may benefit from tailored interventions.

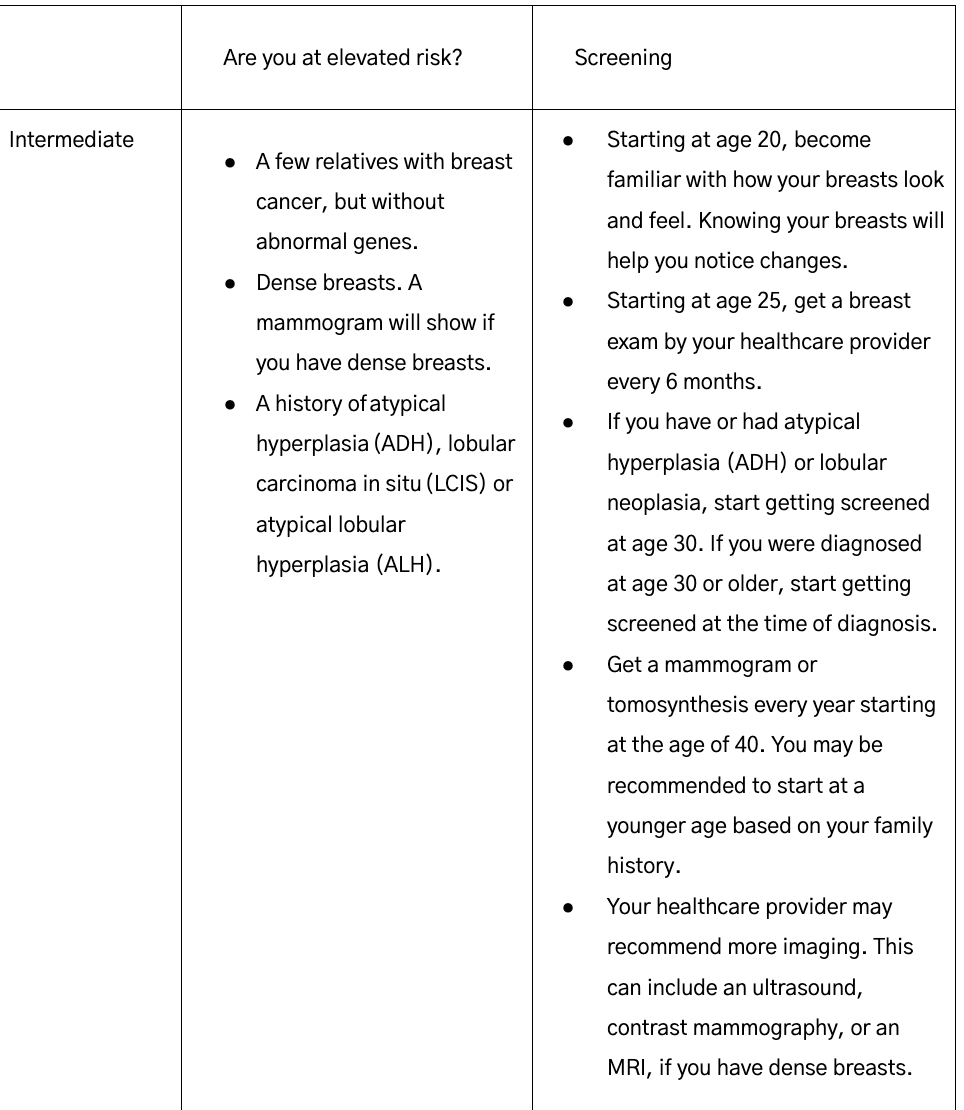

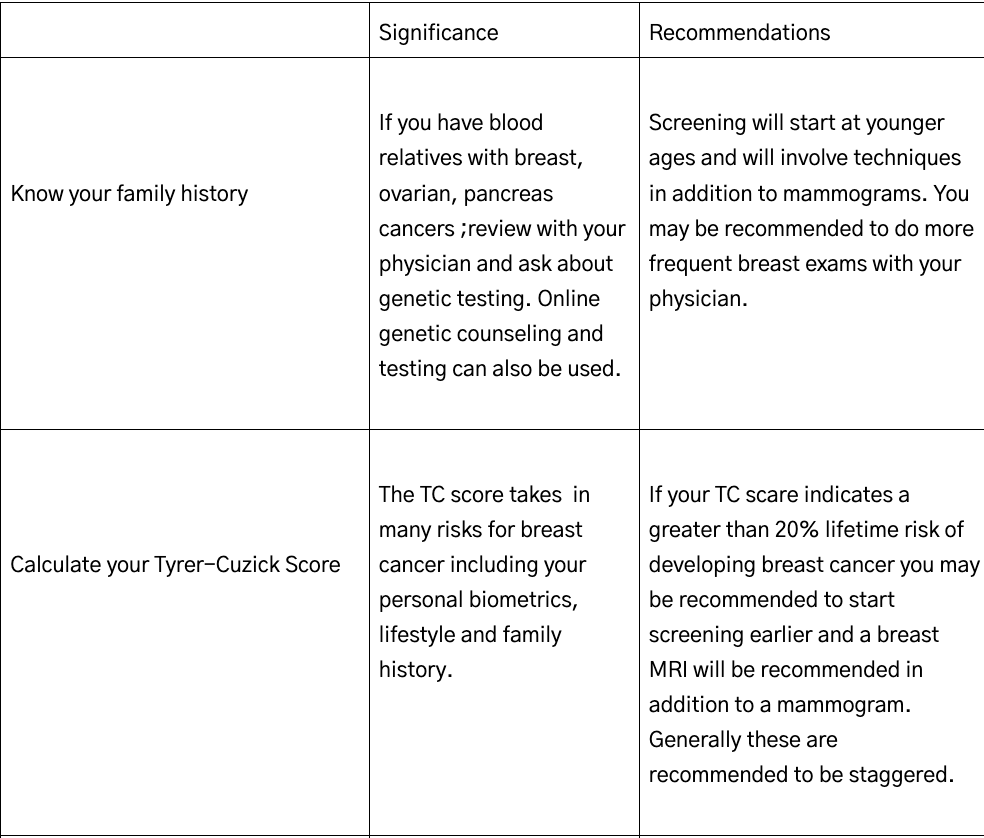

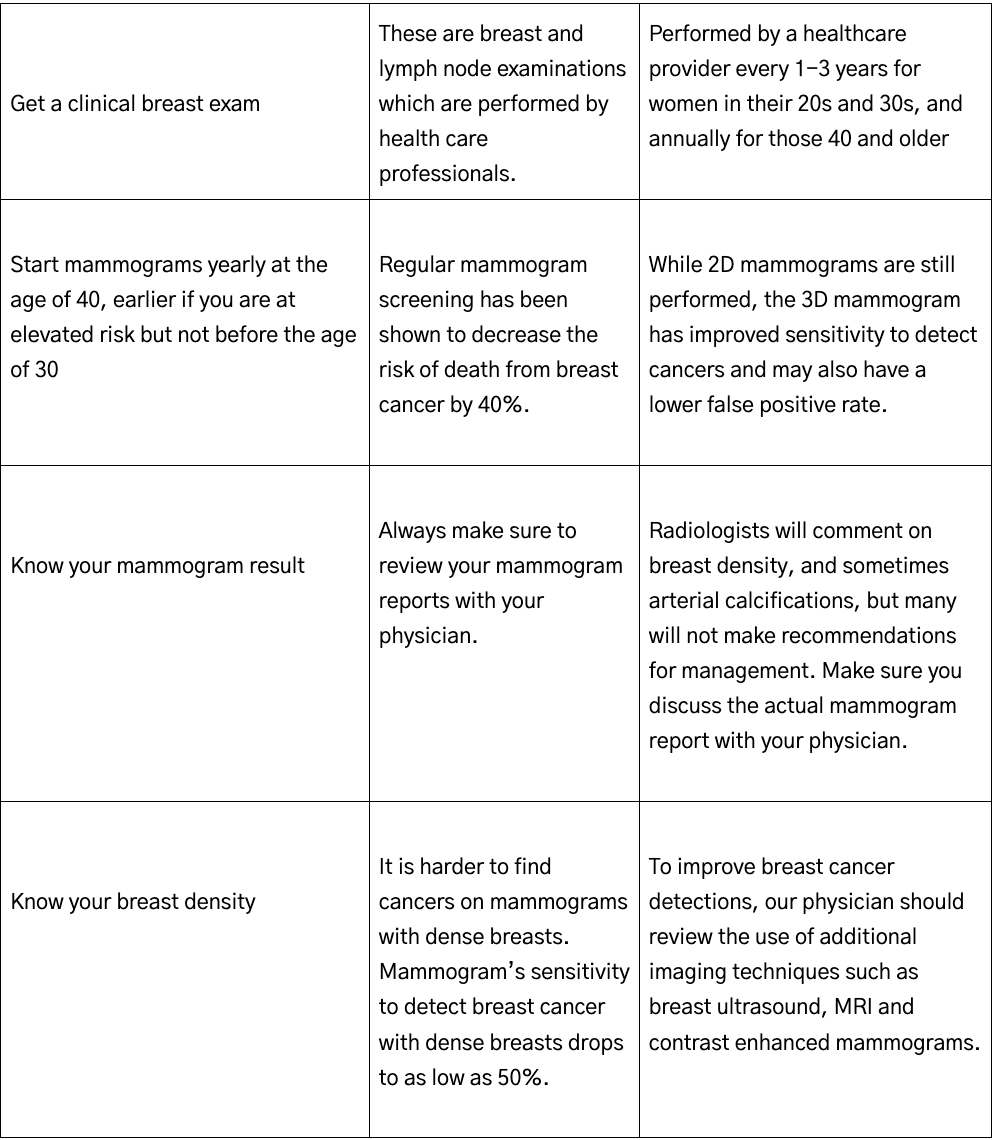

Breast cancer screening remains a cornerstone of early cancer detection and mortality reduction. It is recommended that women start having a mammogram, an x-ray of the breasts, every year at the age of 40, with earlier or additional screening based on risk factors and lifetime risk to develop breast cancer.

For women at higher-than-average risk—such as those with BRCA mutations, a strong family history, or prior chest radiation, or a Tyer-Cuzick Score greater than 20%—annual mammography and supplemental MRI are recommended.

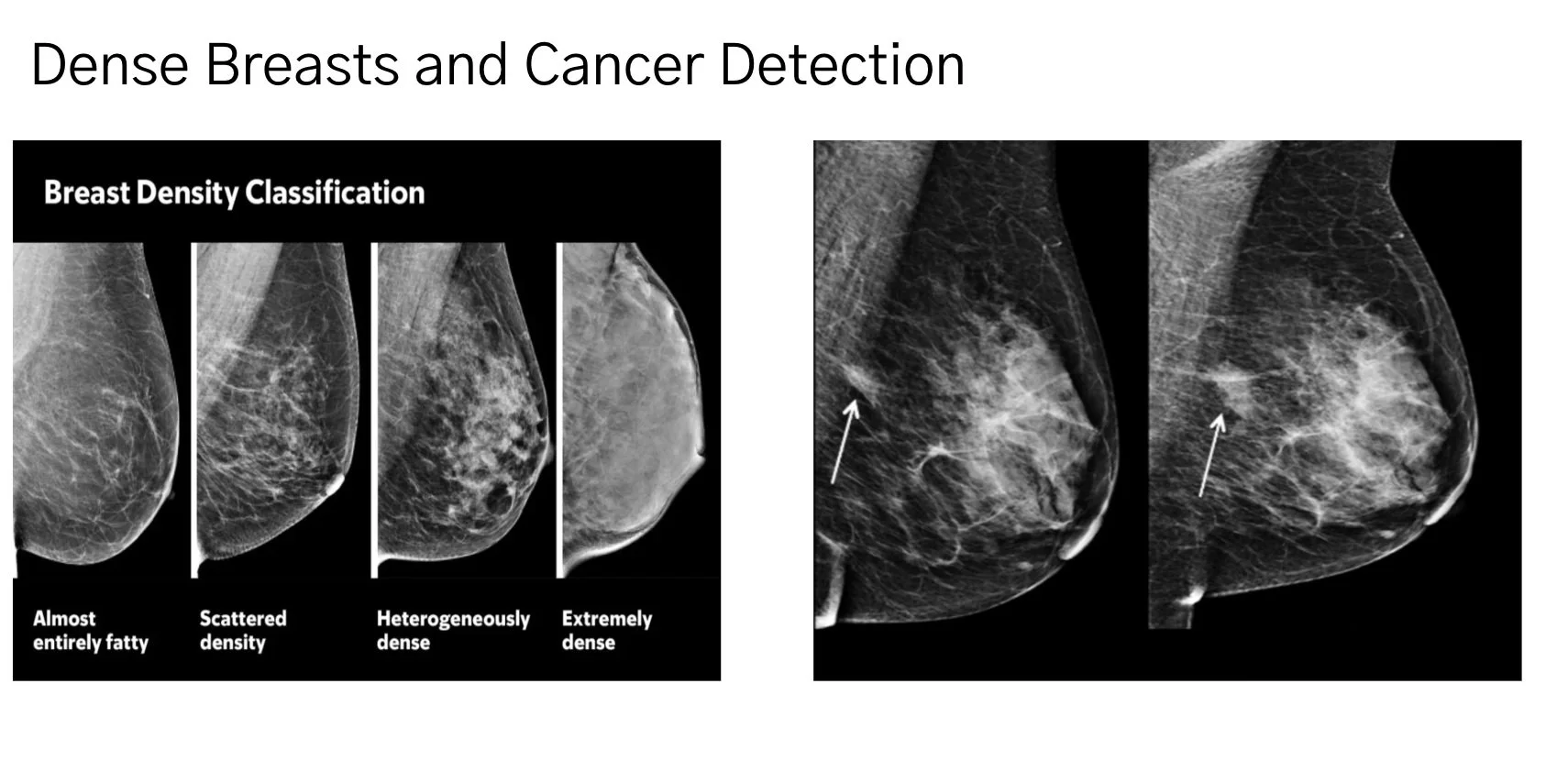

For women who have dense breasts on a mammogram, additional screening such as an USG (ultrasound), breast MRI or contrast enhanced mammogram (CEM) should be considered and reviewed with you. Dense breasts refer to a condition where a woman's breasts have a higher proportion of fibrous and glandular tissue compared to fatty tissue, as seen on a mammogram. This is assessed through breast density categories (A to D, with D being extremely dense). Dense breasts are common, affecting about 40-50% of women. Dense breast tissue appears white on mammograms, which can make it harder to detect cancer, as tumors also appear white. Because of this, women with dense breasts may need supplemental screening, like ultrasound or MRI, for better detection of breast cancer. It is also a risk factor for breast cancer, increasing risk by about 1.5-2 times compared to non-dense breasts. Density typically decreases with age or menopause. Make sure to look at your mammogram report and review the breast density with your physician. Many times, a breast ultrasound will be recommended. Recent data demonstrates however that breast MRI and a specialized type of mammogram, called a contrast enhanced mammogram, pick up more cancers in women with dense breasts. The disadvantage of these additional ultra sensitive tests is they may result in more false positive tests. A false positive happens when the scan suggests something abnormal, like a possible tumor or cancer, but further tests (like a biopsy) show that it’s not actually cancer or anything harmful. It’s like the ultra sensitive test is raising a red flag, but after checking, it turns out to be a harmless spot, such as a benign lump or normal tissue.

Figure 3: Breast Density The left panel shows the categories of breast density. Category D and D are considered dense. The right panel shows how cancer (the arrow) can be difficult to detect on mammograms. The FDA required breast density notification in mammography reports starting September 2024, but the radiologist many times will not make a recommendation on how to further assess your breasts if they are dense, so it is many times up to you or your physician to understand this.

If your screening mammogram is abnormal, the next steps typically involve further evaluation to determine the cause of the abnormality, which may not necessarily indicate cancer. Your physician will likely recommend additional imaging, such as a diagnostic mammogram with more focused views, an ultrasound to assess specific areas, or possibly a breast MRI for a more detailed look, especially if you have dense breasts or high risk factors. In some cases, a biopsy may be suggested to analyze tissue from the abnormal area, with procedures like a core needle biopsy or fine needle aspiration, guided by imaging for accuracy. Your physician will discuss the findings, guide you through the process, and recommend follow-up based on results, which could range from routine monitoring to treatment if needed, ensuring a personalized approach to your care.

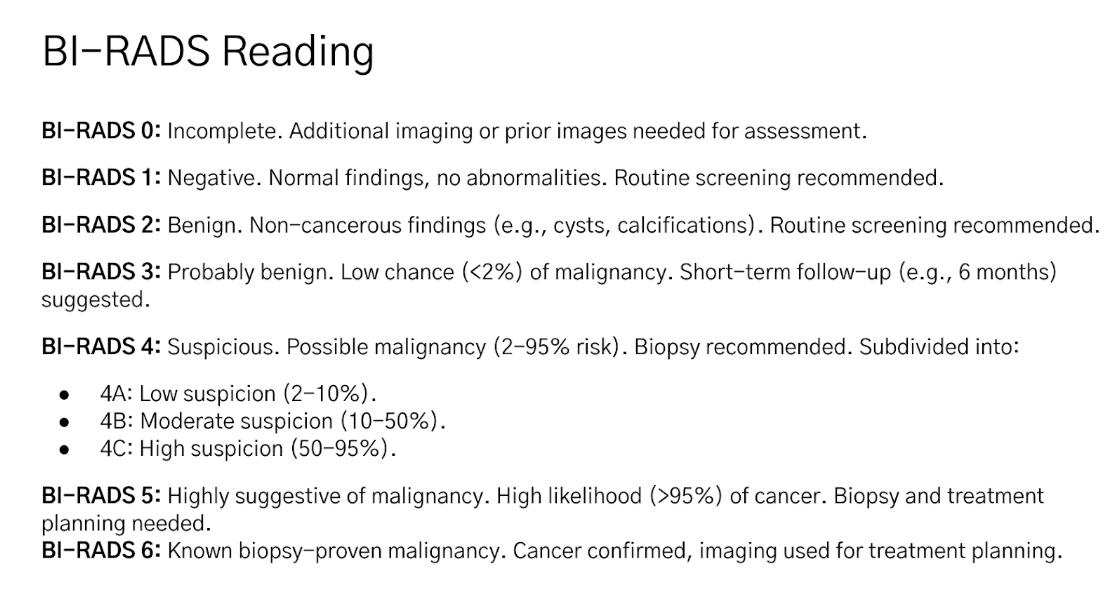

The BI-RADS (Breast Imaging-Reporting and Data System) categories are standardized classifications used by radiologists to describe mammogram findings and assess the likelihood of breast cancer, guiding further management.

FIgure 4: Understand Your Mammogram: The BI-RADS system.

Arterial calcifications can also (and should be) noted on a mammogram report. Arterial calcifications on a mammogram are calcium deposits in the walls of the breast's blood vessels, particularly arteries. They appear as bright, linear, or parallel white lines on the mammogram. These calcifications are usually benign and not related to breast cancer. They’re more common in older women or those with conditions like diabetes, high blood pressure, or atherosclerosis. While they don’t typically require treatment, their presence might prompt your doctor to assess your overall cardiovascular health.

What Happens if I am Diagnosed with Breast Cancer

If you’ve just been diagnosed with breast cancer, take a deep breath—you’re not alone, and there are clear steps to move forward. Start by connecting with a trusted healthcare team, including a breast surgeon and breast medical oncologist, who will guide you through understanding your specific diagnosis, such as the type and stage of cancer. Staging incorporates tumor size, nodal involvement, and presence of metastases, and guides management, which is multidisciplinary and may include surgery, radiation, systemic therapies (endocrine, chemotherapy, targeted agents), and, in select cases, immunotherapy. Ask questions, seek a second opinion if you’re unsure, and consider support from a counselor or breast cancer support group to help process emotions. Gather information from reputable sources, like organizations such as the American Cancer Society (cancer.org) , National Institutes of Health PDQ (cancer.gov) NCCN (nccn.org) , and breastcancer.org to empower yourself. Finally, lean on loved ones for emotional and practical support as you navigate this journey, taking it one step at a time.

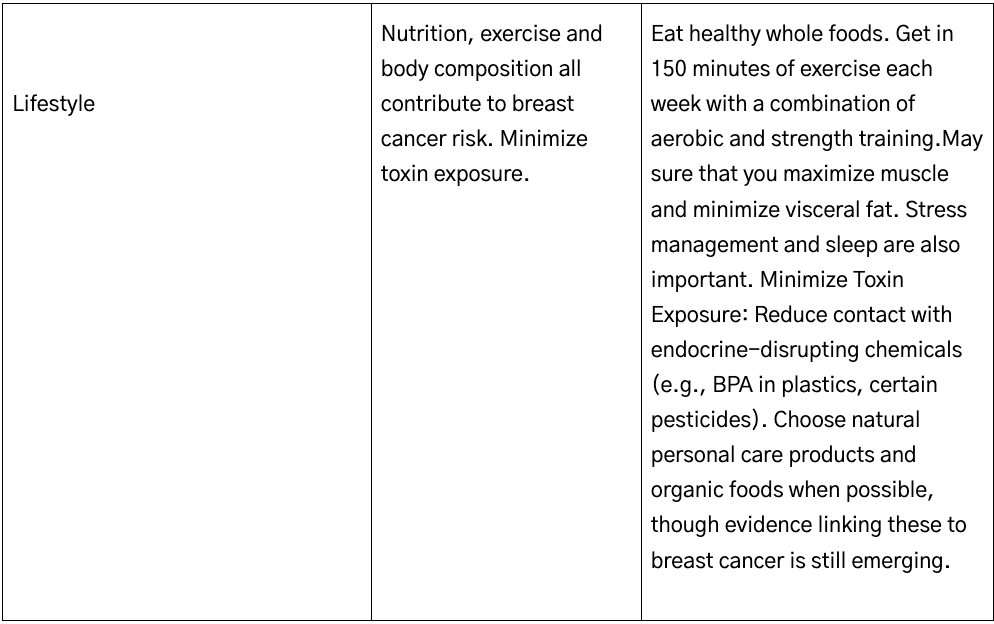

Nutrition for Breast Health

Nutritional strategies for breast health emphasize dietary patterns that are rich in vegetables, fruits, whole grains, legumes, and healthy fats, while minimizing red and processed meats, refined carbohydrates, and alcohol. The Mediterranean diet, characterized by high intake of plant-based foods, olive oil, fish, and moderate consumption of dairy and poultry, has been consistently associated with a reduced risk of breast cancer and improved overall health outcomes. Increased consumption of fiber, polyphenols, omega-3 fatty acids, and foods with a low glycemic index may further contribute to risk reduction, while excessive intake of red or processed meats and high-glycemic foods is associated with increased risk.

For breast cancer survivors, the American Cancer Society and the American Society of Clinical Oncology recommend a dietary pattern high in vegetables, fruits, whole grains, and legumes, with alcohol limited to no more than one drink per day, as higher alcohol intake is associated with increased risk of recurrence and all-cause mortality. Weight management through dietary change is also emphasized, as obesity is a modifiable risk factor for both breast cancer incidence and recurrence. While evidence for the protective effects of specific nutrients (such as vitamin D, calcium, and lignans) is emerging, current consensus supports a holistic, plant-forward dietary approach rather than reliance on individual supplements or foods.

The most extensively studied dietary supplements for breast cancer prevention in high-risk populations include vitamin D, folate, vitamin B6 (pyridoxine), soy isoflavones, and certain phytochemicals such as curcumin, sulforaphane, and epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG). However, the current evidence does not support recommending any of these supplements for breast cancer prevention in high-risk women. Some studies suggest potential protective effects of specific micronutrients (e.g., vitamin D, calcium, folate), but these findings have not been confirmed in large randomized controlled trials, and supplementation should not be recommended for breast cancer prevention outside of correcting documented deficiencies or specific high-risk populations. Some studies suggest for soy isoflavones a possible reduction in estrogen receptor–positive breast cancer risk, but there may be increased risk for estrogen receptor–negative disease and in women with a family history of breast cancer, raising safety concerns. Phytochemicals such as curcumin, sulforaphane, and EGCG show promise in preclinical models, but clinical evidence in high-risk populations is currently lacking.

Exercise for Breast Health

Exercise plays a significant role in breast health and regular physical activity is a modifiable factor that supports breast health by reducing breast cancer risk, improving prognosis, and favorably altering breast tissue biology. Substantial evidence demonstrates that moderate to vigorous physical activity is associated with a lower risk of both premenopausal and postmenopausal breast cancer, with a dose-response relationship observed—higher levels of activity confer greater risk reduction. Mechanistically, exercise is thought to reduce breast cancer risk through several pathways, including lowering circulating insulin levels, reducing adiposity, modulating adipokines, decreasing inflammation, and improving immune function. Randomized trials in high-risk women show that aerobic exercise reduces body fat and visceral adiposity, which are linked to changes in breast tissue characteristics associated with cancer risk.

Impact of Alcohol, Smoking, and Environmental Factors

Alcohol consumption, smoking, and certain environmental factors such as sedentary lifestyle and obesity all increase breast cancer risk, with alcohol being the most consistently and strongly implicated modifiable factor. Reducing or eliminating alcohol intake and tobacco use, along with promoting physical activity, are key strategies for breast cancer risk reduction. Alcohol consumption is an established, dose-dependent risk factor for breast cancer, with even low levels of intake (as little as one standard drink per day) associated with a measurable increase in risk. Multiple large-scale studies demonstrate a linear relationship, with relative risk increasing by approximately 5–12% per additional daily drink, and the effect is observed for both pre- and postmenopausal women. The American Cancer Society and the American Heart Association both state that there is no safe level of alcohol consumption for cancer prevention, and the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) classifies alcohol as a Group 1 carcinogen for breast cancer. The risk is particularly pronounced for hormone receptor–positive subtypes of breast cancer.

Cigarette smoking is associated with a modestly increased risk of breast cancer, particularly among current and long-term smokers, and especially in women who begin smoking before their first pregnancy.

The Gut Microbiome and Breast Health

The gut microbiome has emerged as a significant modulator of breast cancer risk, development, and response to therapy. Dysbiosis in the gut can influence breast carcinogenesis through several mechanisms, including modulation of systemic immune responses, chronic inflammation, and, notably, the regulation of estrogen metabolism via bacterial β-glucuronidase activity, which impacts circulating estrogens and may promote breast cancer. Specific gut microbial taxa have been causally linked to increased or decreased risk of breast cancer subtypes, supporting the concept of a gut microbiota–mammary axis. Modulation of the gut microbiome through diet, prebiotics, or probiotics is being explored as a potential strategy for breast cancer prevention, with evidence suggesting that maintenance of a eubiotic microbiome may reduce risk and improve outcomes.

The breast microbiome itself is distinct from the gut and skin microbiota, with unique microbial signatures identified in both healthy and malignant breast tissues. Alterations in the breast tissue microbiome—characterized by reduced diversity and specific shifts in bacterial taxa—have been associated with tumor presence, subtype, and stage, and may contribute to local immune modulation and carcinogenesis. The interplay between the gut and breast microbiomes, and their combined influence on the tumor microenvironment and systemic immunity, is an area of active investigation with implications for prevention, biomarker development, and therapeutic intervention

Integrative Approaches to Breast Health

Integrative testing, which can include an assessment of estrogen and its metabolites, as well as cortisol levels at multiple time points of the day, is particularly valuable for assessing breast health because it provides detailed insights into estrogen metabolism and related risk factors for breast cancer.

Estrogen metabolism plays a role in breast cancer risk. Estrogen is broken down into metabolites (2-OH, 4-OH, 16-OH) via liver pathways, and imbalances (e.g., favoring 4-OH or 16-OH over protective 2-OH) or poor methylation (clearance) can increase DNA damage and breast cancer risk. Alcohol, as noted earlier, exacerbates adverse metabolism by raising oxidative stress and increasing cancer risk. Women can use results to help guide interventions (e.g., cruciferous vegetables, DIM supplements, or methylation support like folate) to shift metabolism toward protective pathways, reducing breast cancer risk.While supplement support requires additional study, women can consider these approaches after a review of risks and benefits.

Chronic stress elevates cortisol, which can disrupt sex hormone balance, increase inflammation, and indirectly affect breast health. High cortisol may also impair detoxification pathways, increasing oxidative stress linked to cancer. Tests which map daily cortisol and cortisone patterns, indicate DNA damage relevant to breast cancer risk, and directs a woman to stress management strategies such as mindfulness, yoga, supplement support called adaptogens (she Chapter x for complete review of cortisol and stress management), and sleep optimization, reducing cortisol’s impact on breast health.

These types of testing align with an integrative approach to breast health by providing actionable data to complement conventional interventions and lifestyle strategies to optimize breast health. However, it should be used under professional guidance, alongside other diagnostics.

Know Your Risk of Breast Cancer

Navigating Breast Health: Tailoring the Approach

Individualized Plan: Work with a healthcare team (e.g., primary care doctor, oncologist, nutritionist, integrative medicine specialist) to customize strategies based on age, menopausal status, genetic risk, and lifestyle.

High-Risk Women: May need more intensive monitoring (e.g., earlier/more frequent screenings, genetic counseling) and stricter lifestyle modifications.

Cultural and Personal Preferences: Incorporate practices that align with your values, such as traditional dietary habits or spiritual practices, as long as they’re evidence-supported.